These days it is hard to avoid seeing references to Rosalind Franklin whenever DNA is mentioned. In earlier and saner times she might have been mentioned in passing, as someone who made some worthwhile technical contributions. We all know that James Watson and Francis Crick first figured out the structure of DNA in 1953. Franklin was a helper along the way, having taken useful X-Ray photographs, from which deductions were made by Watson and Crick that she did not herself make. But since scientific reputations are subject to inflation too, she is now cast as a co-discoverer of the double-helix structure. That was never a claim that she made herself, nor was it ever made during her own lifetime. Now it is all over the place.

The general demand for female scientists extends to the past as well as the future. There, too, it far exceeds the supply. Consider the bulky five volume Dictionary of 19th Century British Scientists (2004) edited by Alan Lightman. Rubbing shoulders with Charles Darwin, James Clerk Maxwell, Francis Galton, T. H. Huxley, J. F. W. Herschel, Lord Kelvin and other giants are many female figures few would ever have heard of. Botanical illustrators. Teachers. Laboratory assistants. Many of these have no publications to speak of. Where they do, those are typically magazine articles for popular audiences, or books in which their illustrations appear. Even specialists would be hard-pressed to recognize them.

Ever heard of Maria Emma Gray (1878-76)? Her illustrations adorned her husband’s book on mollusks. How about Margaret Gatty (1809-73)? She was, we are told, the author of classics like Parables from Nature (1855-7), illustrating the truths of theology. No doubt solid works in their day, but she was not in any sense a scientist, let alone one fit to keep company with Faraday and Boole. Many, wearisomely many, other examples could be given. Determined browsing of the entries fails to turn up a single worthy inclusion. The implications are far-reaching, since the entry criteria for women seem to have involved no more than the vaguest proximity to science.

The contributors to that dictionary are aware of the incongruity of including marginal figures (and these are plainly very broad margins). They defend their decision to do so by railing against the practice of marginalization! If nobody belongs properly in the margins, if all must have prizes, then we would have to include just about everybody who came into any sort of contact with science in the 19th century. Naturally. there are no male figures of that kind included. They are not needed to make up the numbers, which is really why the marginal females are there at all. The effect is counter-productive. Obscure botanical illustrators, religious tract writers and school teachers are so obviously marginal that they appear ludicrously out of place, and are unfairly diminished as a result. They belong in some other anthology, say of botanical illustrators. But then that would properly include a lot of men too….

The history of the discovery of DNA has been well covered in the past. There is no shortage of excellent sources. Aside from Watson’s own entertaining first-hand pot-boiler, The Double Helix (1968: expanded, annotated and illustrated in 2012), there is Horace Freeland Judson’s The Eighth Day of Creation (1979: expanded in 1996 by Cold Spring Harbor with a lot of Franklin material). Judson’s account is balanced and meticulous, and based on extensive interviews of the principal actors. In it Franklin’s role is described fairly and accurately. An excellent appendix in the 1996 edition clarifies Judson’s position on Franklin further.

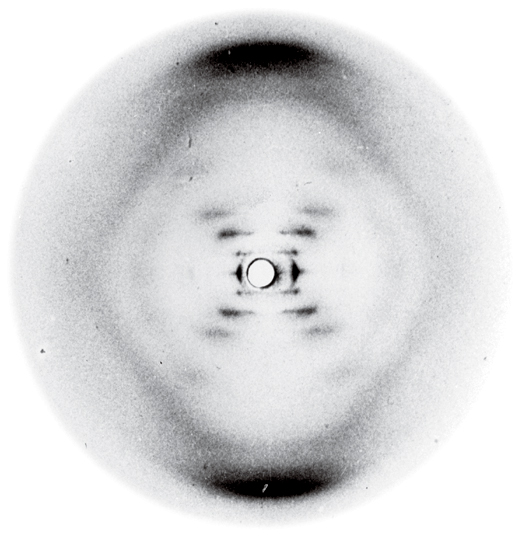

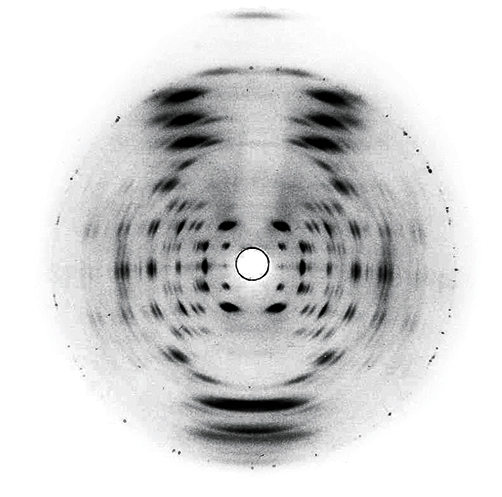

Franklin was an X-Ray crystallographer who took two useful photographs of physical DNA in its spindle form, after a complicated process of extraction from cells, under differing humidity conditions. She did not invent that technique, nor did the idea for taking the photographs originate with her, though she executed them painstakingly with rare skill. Bragg had introduced the technique many years earlier. Less clear examples of her photographs had been taken before the war. The key was getting them sharper, a difficult task, which Franklin had already succeeded at by April of 1952. The photographs showed a diffraction pattern in two dimensions. Working backward from that, the three-dimensional structure which produced the pattern could be reconstructed. Franklin did not do that.

As soon as Watson was shown the photographs by Maurice Wilkins on January 30, 1953, when he visited the dungeons of King’s College. The Watson-Crick team were almost immediately able to reconstruct the structure behind the diffraction patterns: a double helix of chains running externally in opposite directions, bonded together internally, now universally familiar. The key photograph was the B-form, taken under conditions of high humidity.

In the meanwhile, unknown to the broader world, unaware that Watson and Crick had already found it, Franklin speculated through February of 1953 in her private notebooks about the structure of DNA. For the longest time she had concentrated on the A-form X-Ray, mistakenly thinking that it shows that DNA does not have a helical structure, contrary to Wilkins (though this is disputed by Markel, of whom more below). On February 10, having wasted nearly a full year, she finally realized that the crucial photograph is the B-form, and that a helical structure is not ruled out by either form. Too late.

In their first notice of their results, “Molecular structure of Nucleic Acids”, published in Nature on April 25, 1953, Watson and Crick credited Franklin and Wilkins appropriately for their “experimental results” and “ideas”. Franklin was not able to solve the puzzle herself, though some who later read her notebooks, after her early death from cancer in 1958, supposed that she might have been able to get there. But she showed no realization in her private notes that the matching helix strands ran in opposite directions, a critical part of the correct model. She had not even been scooped, because she never got there in the first place.

One reason Franklin did not get there is the fact that she had fallen out with her fellow lab member Maurice Wilkins at King’s College, where she had been based. Wilkins and his colleagues struck her as mediocrities. “There isn’t a first-class, or even a good, brain among them” she had already written to her friend Anne Sayre in March 1952. Worse, “the middle and senior people are positively repulsive and it’s they who set the general tone”. At one stage she confronted Wilkins personally and warned him to stay away from the structure of DNA, which she considered her personal domain! By April of 1953 she had had enough and moved over instead to J. D. Bernal’s crystallography lab at Birkbeck.

Bernal, a devout communist and energetic womanizer, is notable now for his pro-Stalin eulogy written on the death of his beloved leader in 1953. He even won the official Stalin Prize of the USSR. Curiously, Wilkins had also been on the radar of MI5 for some pro-Stalin remarks of his own during the war, when he had worked on the atomic bomb project. With Bernal, Franklin worked on different problems involving the tobacco mosaic virus, when she was not holidaying in Yugoslavia. At the crucial moment she had deserted the field. Later she would complain that those in Bernal’s lab who were not Communist Party members were obstructed. A better fate than “liquidation” to be sure.

In evaluating Franklin’s role in the discovery of the double-helix structure of DNA, it is useful to carefully state the different claims that might be made.

- Rosalind Franklin discovered at least part of the structure of DNA.

- Rosalind Franklin did not discover the structure herself but could have.

- Rosalind Franklin did not discover the structure herself but would have.

Claim 1 is certainly false. She discovered no part of the structure of DNA. She produced some skillful painstaking photographs. Neither Watson not Crick relied on her interpretation of those photographs. All they needed were the photographs and ran with them. Her private speculations in her notebooks after that are not especially relevant. Speculations which fell well short of the mark.

Claim 2 is imponderable. Who can say? Almost anything is possible. Linus Pauling and many others could have discovered the structure too, but they too did not. Certainly Watson and Crick were a much stronger team and always more likely to do so, with Crick’s mathematical skills rare and valuable. Franklin probably needed a collaborator to supply complementary skills that she lacked, but she was temperamently unsuited to that sort of thing.

Claim 3 is certainly false. She would not have. At the very least she was already beaten to it. Moreover Franklin had abandoned the field because of her squabbles with Wilkins and dislike for the King’s College setup. If Watson and Crick had not already solved the puzzle, it would not have been solved by her without another career change and yet more imponderable events.

Why then has so much been made of Franklin, given that she was no more than a skilled technician in this process? It was a slow development, starting in the 1970s with her first biographer, her friend Anne Sayre, whose insubstantial Rosalind Franklin and DNA (1975) catalyzed the process of reinvention. Brenda Maddox—notable for writing almost exclusively about women, even to the extent of writing a biography of Nora Barnacle rather than that insignificant fellow she eventually married, James Joyce—followed with Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA (2002). But Maddox was unembarrassed by any technical knowledge of the field. Now the tumbling has become an avalanche, and each year brings forth more of these productions. Even Chelsea Clinton has, it seems, entered the lists (you will have to locate and read that on your own). Some have also argued that Franklin should have shared the Nobel prize with Watson, Crick and Wilkins, apparently unaware that the Nobel is never awarded posthumously.

Watson is given short shrift in the pro-Franklin literature, but we are not concerned with his personality quirks here, let alone with the ungracious remarks he (and others) made about Franklin’s personal appearance. Wilkins is also harshly treated, criticized for showing Watson the X-Ray photographs. But that is exactly how “open science” ought to be conducted. The photographs were not Franklin’s personal property. Nor was the structure of DNA her personal domain, regardless of her “instructions” to Wilkins. The experimental results were the products of publicly funded research. By sharing them, the process of discovery was accelerated. Since Franklin never solved the puzzle herself, and had in any case moved on to the dubious embraces of Bernal, it is obviously a good thing that her data was not locked up out of sight. We could use more data sharing, not less.

Perhaps the most remarkable of these pro-Franklin creations is Howard Markel’s recent The Secret of Life: Rosalind Franklin, James Watson, Francis Crick, and the Discovery of DNA’s Double Helix (2021). Not because of its scholarship, which is unimpressive where it is not non-existent, but for the way in which it follows the new cultural drift. Ostensibly about the discovery of DNA, it is mostly about Franklin instead. A remarkable shift given that she did not, as we have seen, discover it. No matter! Markel’s technique is not so crude as to make obviously false claims, but rather to elevate his subject through placement out of proportion, describing all her doings in as much detail as possible, giving an exaggerated impression of importance. It is the standby technique of salesmen everywhere.

Mixed in with Markel’s sleight of hand and (what amounts to) choice of italics and font size is the baggage of modern academic life, such as the curious claim that Franklin was up against a world of white male scientists! For this to make sense, we must suppose that Franklin, by virtue of being Jewish, was not herself white.

Franklin, far from being up against anything, came from one of the wealthiest Jewish families in England, established there since the 18th century. They are reliably described as white, which is what her photographs suggest. She had been given every advantage by that, including the very best, or at least the most expensive, schooling available at every stage, culminating at Cambridge. It even included post-graduate work abroad in Paris. At the point where she had taken her photographs, all prerequisites had been met. She was in position and on the case. The only obstacle between her and the structure of DNA was her own ability to find it, to stick the course. She fell well short.

If all you know about a person is some general fact—say that they are female—then you may be forced to make deductions on that basis alone. Your best estimate of that person’s height would be the average height of women. After all, that’s all you know about her. But if you happen to possess a direct measure of her (individual) height, how much attention should you pay to the fact that she is a woman, and that women have a certain average height? Contrary to conventional wisdom, the fact that she is a woman is never wholly irrelevant, even when you know specific facts about her. Conditional probability can be used to to correct your height estimate, which has some error variability. The correction will be very small though, since height can be measured individually to very high accuracy. Here it would make no practical difference.

In Franklin’s case there is a lot more information to condition on. We already know that she was in exactly the right position to make the required discovery. She had funding. She had the job. She had the equipment. She had the data. She had the time. She had the very best education on offer before that. But she had missed the boat and had already moved on. Conditioning this on a general statement about discrimination against women is a forlorn argument. It would require the placing of scales over her eyes while she was taking photographs and constructing models. A bad argument from the start.

As it happens, Horace Judson overlooks the inadmissibility of the “argument from discrimination” to marshal evidence that women were not, in fact, discriminated against in Franklin’s environment. He offers statements from women actually in the laboratory that they were free to conduct research and did so: Dame Honor Fell, Mary Fraser, Sylvia Jackson and others. He estimates that at least 1/3 of the research staff under J. T. Randall, who ran the lab that Franklin was a member of, were women. However it is a mistake to dignify the “argument from discrimination” with this kind of response, because it concedes bad premises which are not advanced in good faith. Anyway, this sort of evidence invariably fails to convince those determined to believe otherwise—the kind of people who advanced the argument in the first place. They have a glib answer. Markel provides it on cue. “Many women today, when reading such a glib dismissal of these hurdles, might shake their heads in disbelief”. The fact that Judson’s women were actually there just counts against them.

One bad argument simply leads to more. But it is important to understand that Markel has, like most of his colleagues, switched paradigms here. The idea is no longer to support conclusions with carefully analyzed evidence, properly weighed and rigorously tested. Contingent statements are brushed aside by necessary deductions from a framework. Historical figures are just illustrative examples in the light of self-evident truths. There is no need to assemble evidence to establish that Rosalind Franklin was discriminated against because she was a Jewish woman. It is enough to identify her as a Jewish woman and Maurice Wilkins as a gentile male. Discrimination follows from that. And not just discrimination, but that miraculous instrument of policy, effective discrimination, which somehow always achieves its nefarious ends without fail. Who would doubt it?

Markel’s book is one long exercise in illustrative examples, in which every single argument or spat Franklin was ever involved in is rehashed and decided in her favour, a miraculous outcome in any other paradigm. Maurice Wilkins emerges as a stage villain, moved about with the omniscience of Tolstoy, with ready access to his innermost feelings and motives. His statements are always “claims”. Any statements favoring Franklin are just read into the record. Any rumor discrediting Wilkins is dangled before the reader.

Let’s restrict ourselves to a single example of this method. Markel is confident that Franklin’s departure from King’s College was “probably” a combination of her own desires and efforts by Wilkins to get rid of her. Interesting if true. No shred, not one nano-scintilla, of evidence is offered by Markel for Wilkins’ supposed role in this. It’s just another illustrative example, immediately deducible from the framework Markel operates within. There is a marvelous efficiency to it all.

But those who think that Markel’s evidence-free methods support the case that Franklin really did discover the structure of DNA must face up to the fact that Markel provides nothing more than a long list of excuses for her failure to find it. No excuse is too weak or implausible. The determined reader will have to endure through woeful examples like the practical jokes played on her in the lab. And the fact that Watson, Crick and Wilkins liked to call her Rosie, even though, Howie tell us, she disliked that.

Providing all these excuses simply concedes the narrower point that is our sole concern here. There is no disgrace in Franklin’s failure. Major figures like Linus Pauling and a host of others failed too. No extraordinary circumstances are needed to explain that. Inflation of her role is due entirely to others, long after her death, determined to use her for their own purposes, a shuttlecock to bat around. As Judson points out, that inflation improperly demeans her real accomplishments, which should rather be accurately described and appreciated in themselves.